Vanity Fair

Plastic Surgery Confidential

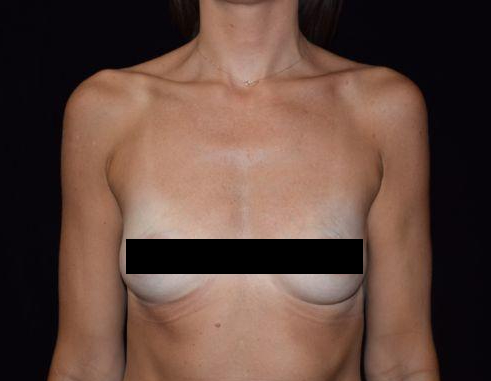

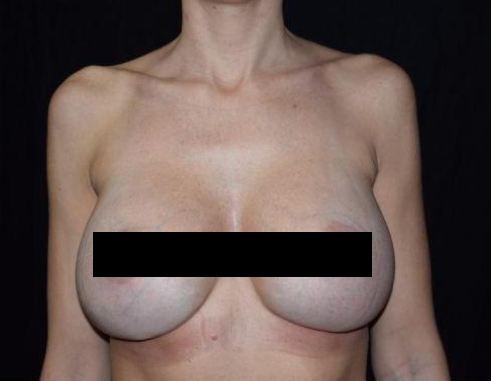

Cosmetic surgery is now so popular that even young, healthy, attractive women are choosing to be “enhanced.” In a quest for insight into this $13 billion industry, the author—a five-foot-nine, 120-pound 27-year-old—went undercover, asking three plastic surgeons what they’d do to her nose, her breasts, and her, uh, “banana rolls.” The answers were as different as the doctors themselves. The author, Melanie Berliet, had consultations with three plastic surgeons to determine what procedures they would recommend. The first, Dr. David P. Rapaport, proposed eliminating her “banana rolls” and “waist wads” and enlarging her bust to a size C, which he called “the Promised Land of Breasts.”

I enter a modest brick elevator building deep in Brooklyn for my third and final appointment. My attitude toward plastic surgery has already evolved from ambivalence to distaste, by way of awe, bitterness, and excessive familiarity. I wonder where this meeting will land me next. The stack of aluminum business cards resting atop a glass desk doesn’t bode well. Dr. Joseph A. Racanelli saunters in and takes his seat. He’s a muscular man with spiky, gelled hair and a degree from the Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine. I can’t say I’m surprised to see him gripping a protein shake in his right hand.

“Despite my general discomfort with superfluous references to a higher power, I feel the urge to jump out of my seat and give Dr. Racanelli a standing ovation.”

He goes through the standard health questions, then asks, “How can I help you today?” “I was just hoping to get a professional opinion about my options in terms of plastic surgery.” The doctor squints and replies, rather emphatically, “The way it works is: you tell me if something specifically bothers you, and I’ll tell you if I can address it. But I’m not here to sell you services or goods, because there may be something that you don’t see that I see.” And you won’t share?,” I ask, somewhat startled.

Dr. Racanelli explains that he has an ethical problem with pointing things out, because he’s heard of cases in which patients felt they were talked into a procedure. He continues, “If there’s a specific area of concern, then you and I can discuss it at length … I’m not here to, like, pitch you.” “Is it a legal problem?,” I ask. “No. Not a legal problem. It’s just the way I like to do things.” In that case, I tell him, I’d like to talk about my nose and boobs. Satisfied, the doctor proceeds.

Most of what he says is familiar. He says I’m tall enough to carry a full C-cup, and observes that my nose has a “dorsal hump” and a “bulbous tip.” “Is there a way to image what it might look like?” “There’s a way to image, and it’s a very successful marketing tool,” he replies. “I do not do it, and the reason is: the only person who knows what your nose is going to look like after surgery is God.” Despite my general discomfort with superfluous references to a higher power, I feel the urge to jump out of my seat and give Dr. Racanelli a standing ovation.

“If there’s a specific area of concern, then you and I can discuss it at length…I’m not here to, like, pitch you.”

He eventually leads me to an examination room, instructs me to undress, and leaves. He returns for the inspection, accompanied by a female nurse. After looking me over, he declares, “A full C would look great on you.” Then I ask him about liposuction. “No. Definitely not. You do not need lipo,” he says, letting out a chuckle that I wish I could bottle and fling in Dr. Rapaport’s face.

Back in the office, I ask Dr. Racanelli, who is 35, what cosmetic procedures he’s had done himself. The answer: a nose job at age 15, two hair transplants, and Botox injections in his forehead. “I believe in cosmetic surgery,” he concludes, smiling.

Dr. Racanelli’s enthusiasm is infectious, but I don’t feel pressured by him. I pay the $100 consultation fee and receive a statement detailing the initial quote for breast and nose surgery: $17,500.

All three of the doctors I met during my foray into the realm of plastic surgery left a lasting impression on me. Dr. Rapaport unwittingly dismantled my self-esteem, Dr. Heller patched it back up, and Dr. Racanelli reminded me that how I look should be my choice. As for plastic surgery itself, I can’t say that I’m against it. For every Tara Reid, there must be 20 Marias or Dr. Racanellis, whose lives have been quietly enriched by procedures that made them look a little more perfect—if only in their own eyes. That said, I’ve decided (for now) to hold on to the genetic hand I was dealt. Partly, I can’t afford to make Melanie 2.0 a reality; partly, I’m haunted by the classic Twilight Zone episode in which people select their appearance from menus upon coming of age; and partly—no, largely—I need to believe in the character-building powers of the flaws that make me me.

Call me stupid, stubborn, or ugly. Just don’t pinch my waist wads.